by L Richardson

American art was hijacked by a cultural cartel that replaced our cherished traditions with chaos and theory. We once celebrated Norman Rockwell’s portraits of American life, Thomas Eakins’ masterful realism, and other artists who honored family, faith, and liberty. However, during the mid-20th century, three unelected critics—famously dubbed the “kings of Cultureburg” by Tom Wolfe in his book The Painted Word—orchestrated a silent coup against beauty itself[11].

Leo Steinberg, Clement Greenberg, and Harold Rosenberg transformed our artistic landscape without the consent of the American people. Steinberg amassed over 3,500 prints spanning 500 years of art history[2] and used this collection to legitimize Pop Art’s consumer culture decay. Meanwhile, Greenberg pushed the radical position that the best avant-garde artists were emerging in America rather than Europe[11]. [35] At the same time, Rosenberg coined the term “Action Painting” in 1952 for what later became known as abstract expressionism[12]. Together, these critics hijacked our cultural institutions and betrayed our Republic’s artistic inheritance. As a result, craftsmanship was abandoned, beauty scorned, and our museums filled with works that mock rather than uplift the American spirit. This wasn’t a natural evolution—it was a deliberate theft of our cultural heritage that continues to undermine our conservative values and national identity to this day.

The Rise of the Big Three Critics

Image Source: The Guardian

Three intellectuals commandeered American art criticism in the mid-20th century, fundamentally altering what counted as “great art” in America. Their ascent wasn’t accidental but calculated—a deliberate effort to displace our nation’s artistic heritage with theories that served their intellectual agendas.

Clement Greenberg emerged first. Born in New York to Jewish immigrants from Lithuania, Greenberg initially studied English literature before gravitating toward art criticism[13]. His breakthrough came with his 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” in Partisan Review, which established him as a formidable voice in the art world[13]. In this foundational text, Greenberg viciously attacked popular and realist art—the very paintings that ordinary Americans cherished—dismissing them as mere “kitsch” or trash. Subsequently, he served as art critic for The Nation from 1942 to 1949, beginning almost three decades of dictating American artistic taste[14].

Greenberg’s approach was dogmatically formalist—he refused to discuss the meaning or content of paintings, focusing exclusively on formal elements like shape, color, and line[14]. This approach deliberately stripped art of its moral, spiritual, and patriotic dimensions, reducing it to abstract technical elements. Furthermore, Greenberg positioned himself as the “curator, custodian, brass polisher, and repairman” of Jackson Pollock’s reputation15. He convinced the art establishment that Pollock’s chaotic “drip” paintings represented authentic genius, essentially crowning himself kingmaker of American art.

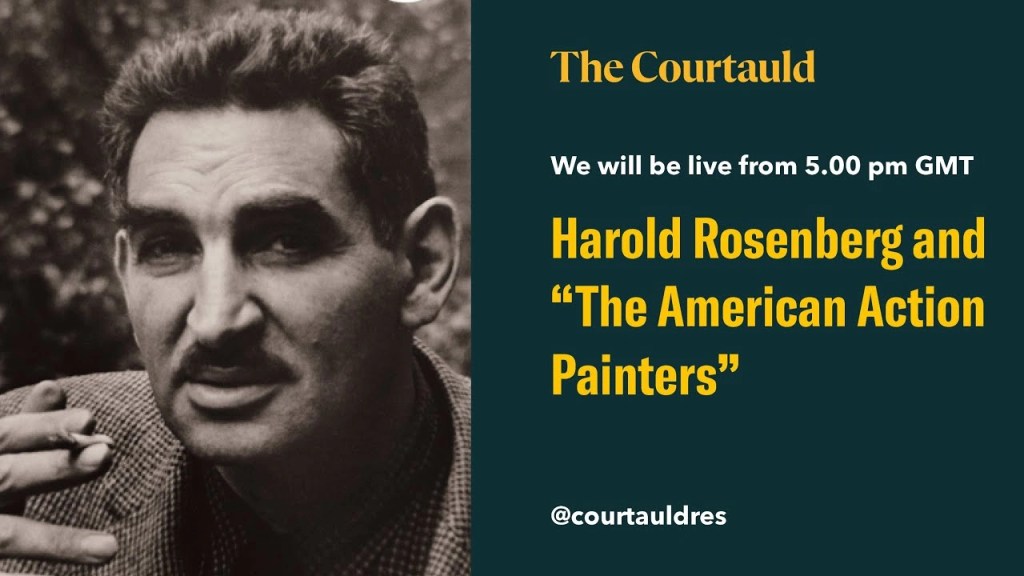

Harold Rosenberg, another New York intellectual, entered the scene with equally destructive force. After earning a law degree, Rosenberg gravitated toward New York’s bohemian circles[14]. His defining moment came in 1952 with his essay “The American Action Painters” in Art News, which introduced the term “Action Painting” [13]. In this influential piece, Rosenberg declared that the canvas was no longer a surface for creating pictures but “an arena in which to act “[14]. Essentially, he elevated the artist’s self-indulgent process above the finished work, glorifying chaos over craftsmanship.

This sparked a bitter rivalry between Greenberg and Rosenberg. However, both men ultimately pursued the same goal: dismantling America’s artistic tradition. Indeed, Rosenberg became the dominant critic of the 1950s, inspiring a new generation of gestural painters who abandoned representation altogether[14].

Leo Steinberg completed this triumvirate of cultural saboteurs. Unlike his counterparts, Steinberg focused on legitimizing Pop Art—bringing soup cans and comic strips into the hallowed halls of high culture. Through his writings, Steinberg helped elevate Andy Warhol’s commercial imagery and Roy Lichtenstein’s comic book appropriations to the status of “serious art.”

These three critics operated within what Tom Wolfe aptly termed “Cultureburg”—a closed Manhattan elite comprising critics, museum directors, and wealthy patrons. Within this insular world, they developed theories that most Americans found incomprehensible. Yet, these theories nonetheless determined what appeared in our nation’s prestigious museums and galleries.

Accordingly, the Big Three succeeded because they captured the institutional machinery of American art. Through their positions at influential publications like The Nation, Art News, and The New Yorker, they controlled the discourse. They cultivated relationships with museum directors who implemented their vision. Additionally, they courted wealthy collectors who spent fortunes acquiring the “correct” artists they championed.

Before their rise, American art celebrated our nation’s values, landscapes, and people. Thomas Eakins painted the nobility of ordinary Americans with technical mastery. Norman Rockwell captured our traditions and family life with warmth and skill. Nevertheless, Greenberg, Rosenberg, and Steinberg worked tirelessly to ensure these artists were relegated to the margins—mere “illustrators” unworthy of serious consideration.

The ascent of these critics wasn’t merely an aesthetic shift but a profound cultural disenfranchisement. They didn’t just change American art—they stole it from the American people.

Clement Greenberg – Prophet of Flatness

Image Source: The Collector

- “Kitsch is vicarious experience and faked sensations.” — Clement Greenberg, Influential American art critic, leading advocate of Modernism.

Clement Greenberg, the self-appointed high priest of Modernism, constructed the intellectual framework that would systematically degrade American artistic traditions. As the most influential critic of his generation, Greenberg didn’t merely comment on art—he wielded his pen like a weapon against the aesthetic values most Americans cherished.

In 1939, the essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” mocked popular/realist art as trash.

In 1939, Greenberg published his manifesto “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” in Partisan Review, establishing himself as a formidable voice in the art world[11]. This Marxist-influenced essay launched a frontal assault on the art that ordinary Americans appreciated. Greenberg contemptuously labeled popular and realist art as “kitsch”—mechanical, formulaic work that offered only “vicarious experience and faked sensations” [16]. He dismissed such art as “the epitome of all that is spurious in the life of our times “[16].

Greenberg’s essay drew a stark line between what he termed “true avant-garde art” and the “debased and academicized simulacra of genuine culture” consumed by the working class[11]. For Greenberg, the art that spoke to everyday Americans—that celebrated their values, depicted their lives, or stirred their patriotic sentiments—was beneath contempt. He insisted kitsch “pretends to demand nothing of its customers except their money—not even their time” [16]. [36]

His contempt for realism wasn’t simply an aesthetic preference—it represented a fundamental rejection of art that served as the cultural expression of American identity. Through his position at influential publications like The Nation (1942-1949), Greenberg gained the institutional power to enforce this division[17]. His intellectual arrogance became the model for the Manhattan art elite who followed him.

Elevated Pollock’s “drip” paintings as genius.

Having demolished traditional American art, Greenberg needed new heroes to champion. He found his perfect vehicle in Jackson Pollock, whose chaotic drip paintings epitomized the rejection of representation, narrative, and traditional craftsmanship. Greenberg famously declared Pollock “the greatest painter this country has produced “[18]—a radical claim that carried enormous weight given his growing influence.

Greenberg’s theoretical justification for Pollock’s seemingly random splatters relied on his concept of “flatness.” He insisted painting’s highest purpose was acknowledging the flat canvas, arguing Pollock’s webs of paint created “an oscillation between an emphatic surface and an illusion of indeterminate but somehow definitely shallow depth” [19]. This glorification of flatness deliberately stripped art of its capacity to convey moral meaning, historical narratives, or patriotic sentiments.

Under Greenberg’s guidance, American museums elevated these unintelligible abstractions above works that actually spoke to American citizens. He insisted that “formalist painting…used art to call attention to art” [20]—effectively severing art from its traditional role of uplifting the public, celebrating shared values, or commemorating national achievements.

Notably, Greenberg rejected political art as “aesthetically inferior” and insisted art “solve[d] nothing, either for the artist himself or for those who receive his art “[20]. This nihilistic perspective stripped art of its communal purpose, replacing it with an empty formalism that only elite insiders could appreciate.

Greenberg’s influence wasn’t merely academic—it fundamentally transformed American cultural institutions. Museum directors, gallery owners, and wealthy collectors all bowed before his pronouncements. His dogmatic assertions about “quality” and “advanced” art shaped acquisitions policies at major institutions for decades, despite never clearly defining these concepts[20].

The constitutional and libertarian implications were profound. A single unelected critic had seized control of America’s artistic inheritance without the consent of the governed. Instead of allowing a natural marketplace of taste to flourish, Greenberg established what amounted to an aesthetic dictatorship. This wasn’t artistic evolution—it was cultural theft executed with surgical precision.

Harold Rosenberg – Apostle of Action

Image Source: YouTube

Harold Rosenberg, once a lawyer and poet, emerged as the second member of the triumvirate that commandeered America’s artistic identity. Alongside Greenberg, Rosenberg systematically dismantled traditional American aesthetics, yet his approach proved even more destructive to our cultural inheritance.

Coined the term “Action Painting.”

In December 1952, Rosenberg published his groundbreaking essay “The American Action Painters” in ARTnews, introducing a term that would fundamentally alter how art was understood[21]. This essay, adopted as Abstract Expressionism’s manifesto, had a profound effect on the artistic landscape of 1950s New York[22]. Rosenberg’s most famous declaration asserted that “at a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act… What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event” [23]. [37]

Through this radical redefinition, Rosenberg specifically attacked the very essence of artistic creation. No longer was a painting meant to represent anything—beauty, faith, family, or nation. Hence, the canvas became merely a record of the artist’s physical movements, stripped of any responsibility to communicate with viewers or uphold cultural traditions.

Rosenberg’s label “Action Painting” quickly became a favored alternative to “Abstract Expressionism,” precisely because it made modern art seem more accessible to the public[23]. Therefore, this clever linguistic move helped normalize what was a rejection of America’s artistic heritage, making it easier for ordinary citizens to accept unintelligible canvases in their national museums.

Elevated chaos and self-indulgence over skill and craft.

Whereas Greenberg emphasized formalism, Rosenberg positioned himself squarely opposite, focusing on the existential act of creation[22]. This approach deliberately elevated the artist’s chaotic self-expression above craftsmanship, technical skill, or aesthetic beauty. Furthermore, he insisted that “a painting that is an act is inseparable from the biography of the artist” [23], effectively making art purely subjective and immune from traditional standards of quality. [37]

Particularly telling was Rosenberg’s belief that action painters worked “almost without regard for conventional standards of beauty”. [37] Consequently, he celebrated this rejection of beauty as an achievement—an “authentic expression of individuality.” This perspective justified years of “chaotic subsistence and verbal—and physical—brawling” among artists[24], glorifying disorder both on canvas and in life.

Rosenberg’s theory deliberately challenged Greenberg’s view that American art evolved from European Modernism [23]. For Rosenberg, abstract expressionism represented a complete rupture with tradition—not an evolution but a revolution. Simultaneously, this positioning helped him establish his own intellectual territory against his rival critic. Yet, both men ultimately pursued the same goal: dismantling America’s artistic tradition.

In his essay “Everyman a Professional,” Rosenberg explicitly acknowledged the elitist nature of modern art: “The public receives the work in the form of ideas into which it has been translated. Thus, every modern work of art is in essence criticism” [23]. [37] This admission reveals the fundamental disconnect between these artworks and ordinary Americans. Since the public couldn’t appreciate these works directly, they needed critics like Rosenberg to translate their significance.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_Rosenberg

Rosenberg’s intellectual plan from the outset was to “rewrite socialist theory by granting the individual, or ‘hero’ as he called him, a central place in Marx’s dialectical take on history “[25]. [38] Unsurprisingly, his ideas gained traction first in leftist publications like Partisan Review, Commentary, and Dissent[25].

This Marxist foundation should raise immediate concerns for conservatives. Through his influential position at ARTnews and later as a professor at prestigious universities, Rosenberg helped install an art movement that rejected America’s cultural values while cloaking itself in revolutionary language. His theories didn’t merely change painting techniques—they represented a fundamental attack on the aesthetic foundations of our Republic.

Leo Steinberg – Priest of Pop

Image Source: Singulart

The final member of this influential trio, Leo Steinberg, completed the cultural coup by elevating consumerism and commercialism to the status of high art. Unlike his predecessors, who focused on abstract painting, Steinberg deliberately blurred the boundary between advertising and art, enabling the wholesale invasion of American museums by popular culture’s most banal elements.

Legitimized Warhol’s soup cans and Lichtenstein’s comic strips as “culture.”

At a pivotal December 1962 symposium at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Steinberg emerged as Pop Art’s most vocal defender. When established critics like Hilton Kramer and Dore Ashton questioned whether soup cans and comic strips could even qualify as art, Steinberg provocatively responded: “That’s one of the best things about it, to be provoking this question” [26]. This calculated defense explicitly endorsed confusion as a virtue—directly attacking the clarity and purpose that had defined American artistic traditions.

Steinberg’s rationale fundamentally changed how art was evaluated. He argued that “the artist does not simply make a thing, an artifact… What he creates is a provocation, a particular, unique, and perhaps novel relation with the reader or viewer” [26]. [39] Through this intellectual sleight-of-hand, Steinberg shifted focus from the artwork itself to the viewer’s reaction—removing all objective standards for judging artistic merit.

The economic impact of this critical endorsement was staggering. In July 1962, Andy Warhol’s first solo exhibition featured 32 Campbell’s soup can paintings—one for each flavor. Warhol sold the entire set for just $1,000; by 1996, when the Museum of Modern Art acquired it, the collection was valued at $15 million. This astonishing price inflation revealed the real function of critics like Steinberg—creating artificial scarcity and value for works that required minimal skill or craftsmanship.

Steinberg’s influence on American cultural institutions was profound. He built his reputation by being among the first to recognize the supposed “value” of Pop Art[2]. He was credited with introducing the term “postmodern” to describe the work of artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns[2]. Importantly, his expertise in prints made him particularly attuned to the reproduction-based techniques of Pop artists who were appropriating mass media imagery[2].

By 1960, Steinberg had already announced that “Abstract Expressionism was history and that the next wave had come in with Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns” [3]. [40] His 1962 Harper’s essay “Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public” directly challenged Greenberg’s distinction between high art and popular culture, making a seemingly democratic appeal: “May we then drop this useless, mythical distinction between—on the one side—creative, forward-looking individuals whom we call artists, and—on the other side—a sullen, anonymous, uncomprehending mass, whom we call the public?” [3] [40]

This apparent populism masked a more insidious agenda. Steinberg wasn’t truly advocating for art that spoke to ordinary Americans—he was legitimizing works that mocked American consumer culture while simultaneously profiting from it. His critical vocabulary introduced terms like “hijack,” “raid,” “echo,” “recycle,” and “appropriate” into art criticism[2], normalizing the theft of commercial imagery as a legitimate artistic strategy.

Across his critical career, Steinberg held Lichtenstein and Warhol “in high esteem” [26], specifically valuing their appropriation of advertising and comic strips—the very cultural products most Americans consumed without pretension. By elevating these works to museum status, Steinberg effectively told ordinary citizens that their cultural preferences were simultaneously worthy of mockery and exploitation.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leo_Steinberg

Cultureburg: The Art Cartel

In 1975, journalist Tom Wolfe fired a devastating broadside at the art establishment with his slim volume The Painted Word. This 121-page manifesto exposed how modern art had abandoned visual experience in favor of becoming mere illustrations of critics’ theories[28]. Wolfe’s central insight was profoundly simple: painting had become subservient to words.

Tom Wolfe’s term, The Painted Word: art became theory, not painting.

Wolfe methodically traced what he saw as modern art’s devolution: “In the beginning, we got rid of nineteenth-century storybook realism. Then we got rid of representational objects. Then we got rid of the third dimension altogether and got really flat (Abstract Expressionism). Then we got rid of airiness, brushstrokes, most of the paint, and the last viruses of drawing and complicated designs” [28]. [41]

This process culminated in what Wolfe sarcastically called art’s “final flight,” where it “climbed higher and higher in an ever-decreasing, tighter-turning spiral until… it disappeared up its own fundamental aperture… and came out the other side as Art Theory!” [28]. [41] Painting hadn’t evolved naturally—it had been hijacked by words, becoming “literature undefiled by vision “[28].

“Cultureburg” = a closed Manhattan elite of critics, museums, and plutocrats.

Moreover, Wolfe identified who orchestrated this theft. He estimated that “the group of people who knew anything about, cared about, or possessed any power to affect contemporary art was vanishingly small, ‘approximately 10,000 souls—a mere hamlet!’” [29]. This insular village he named “Cultureburg”—a closed society of Manhattan critics, museum directors, and wealthy collectors who dictated artistic value[1].

In contrast to natural cultural evolution, this art cartel operated as a social clique where “bohemia (the artists) and le monde (collectors and trustees) share a mutual goal—to be different, to separate themselves from the bourgeoisie” [1]. Curiously, this supposedly revolutionary movement required the financial backing of society’s wealthiest members.

Ordinary Americans excluded from decisions; beauty replaced by dogma.

Ultimately, ordinary citizens found themselves completely locked out of artistic decision-making. As Wolfe noted, the art world had become “a closed place, a ghetto of sorts, that even the press cannot penetrate” [1]. Within this fortress, critics like Greenberg, Rosenberg, and Steinberg “spin a continuum of alchemy that becomes modern art; they write critical theory that influences and even creates painters “[1].

As a consequence, American museums are filled with works divorced from public understanding. Even today, as one defender of art world elitism bluntly states: “I just think dumb people, rich or poor, should keep their noses out of art. It drags the whole tone down” [30]. [42] This arrogant sentiment perfectly captures Cultureburg’s contempt for ordinary Americans’ aesthetic preferences.

Beyond this closed circle, Wolfe observed, “there still aren’t very many people in the world for whom the art of our time has any direct relevance whatsoever. It’s too off-putting, it’s too hard, it’s too limited. It’s over-protected. There are too many barriers” [29]. This wasn’t accidental but by design—a deliberate construction of barriers between Americans and their cultural inheritance.

In particular, Wolfe’s devastating critique exposed how America’s artistic tradition had been usurped without democratic consent. This wasn’t merely an aesthetic shift but a cultural coup—one that systematically excluded the American people from determining their own artistic heritage.

The National Cost

Image Source: Vox

The cultural theft orchestrated by Greenberg, Rosenberg, and Steinberg wasn’t merely theoretical—it extracted a devastating practical cost from American society. Their influence fundamentally reshaped our cultural institutions with consequences that continue to ripple through generations of Americans.

Museums filled with canvases that confuse, mock, or degrade — not inspire.

Upon entering America’s prestigious art museums today, visitors encounter works deliberately designed to confuse or alienate them. As an unfortunate result of the critics’ takeover, these institutions now showcase pieces that mock rather than celebrate our national identity. The art establishment’s focus shifted from visual experience to theoretical justification, leaving ordinary Americans disconnected from their cultural heritage.

Universities trained students to despise beauty, patriotism, and tradition.

Throughout higher education, the pseudo-intellectualization of art-making has systematically undermined traditional values. Craftsmanship has been deliberately downplayed in universities[31], creating generations of artists lacking fundamental skills. Art history became separated from studio practices—often taught in entirely different departments[31]—ensuring students could not connect their work with historical traditions. In place of technical instruction, critiques now consist of “deconstruction of meaning, intent, and philosophy” [31] while ignoring visual construction. This academic environment produced graduates who believe that “verbal gymnastics… can compensate for a lack of skill” [31], as rhetoric outstripped picture-making abilities.

Realist heritage (Eakins, Rockwell, Benton) lost its prestige.

Given these developments, America’s realist painters were systematically erased from the artistic pantheon. The fundamental conflict was simple: “the figure is complex to depict successfully “[31], yet our great realists mastered this challenge. Realistic representation required discipline, patience, and technical skill—precisely the qualities rejected by the new art establishment. As well as sidelining accomplished masters like Thomas Eakins, this shift meant contemporary realist painters faced automatic exclusion from prestigious galleries and critical recognition.

Consequence: Two generations raised on irony, nihilism, and ugliness.

The outcome has been catastrophic. Beyond mere aesthetic preference, this cultural coup trained two generations of Americans to embrace ugliness as sophisticated while dismissing beauty as naive. Young artists seeking careers learned that “exhibition record, preferably in the ‘right’ galleries” [31] mattered more than genuine artistic development. This system diverted attention “from the uninterrupted and serious pursuit of learning” [31], creating artists more concerned with theoretical justification than visual communication.

Clearly, this wasn’t just about paintings on walls—it was about America’s soul. By severing our connection to beauty, the critics undermined our cultural confidence. They divorced artistic expression from the values that built our Republic.

Constitutional & Libertarian View

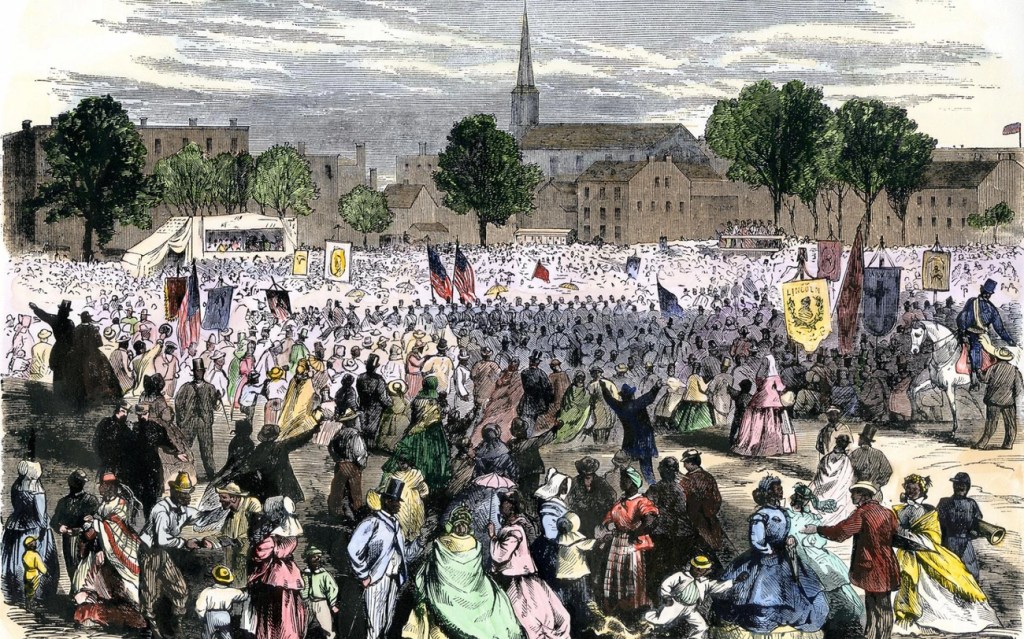

Image Source: National Museum of African American History and Culture … [43]

Beyond the aesthetic damage inflicted upon American art, the critical triumvirate’s takeover represents a fundamental violation of our founding principles. This cultural coup stands opposed to the core values that define our Republic.

Constitutional: Critics seized cultural authority without the consent of the governed.

Democratic power in America derives from the consent of the governed[5]. Yet Greenberg, Rosenberg, and Steinberg seized control of our cultural institutions without any mandate from the American people. Throughout history, such cultural overreach mirrors patterns seen in authoritarian regimes. In 1930s Germany, the Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda led the Reich Chamber of Culture, taking control of cultural production[5]. More recently, Poland’s Law and Justice Party appointed ministry officials who installed party loyalists to lead national theaters without following required expert recommendations[5]. The American art establishment created a similar power structure—unelected critics dictating artistic value while dismissing public preferences.

Libertarian: They crushed the natural marketplace of taste — a cartel dictating value.

Free markets accelerate innovations in the arts much more efficiently than centralized funding or control[32]. Historically, the Renaissance, Enlightenment, Romantic movement, and Modernism all brought art further into market exchange[33]. Following this natural evolution, the most critical work in painting and sculpture became commodities sold in an open marketplace[33]. By contrast, Cultureburg’s critics constructed an artificial value system where theory trumped public appeal. The NEA later formalized this approach—an institution with an impossible mandate trying to deliver the benefits of aristocratic arts spending while remaining accountable to a political system based on the rule of law[33].

Republican/Nationalist: This was cultural subversion — stripping America of beauty, faith, and patriotism.

The cultural elite’s obsession with associating creative works primarily with political, social, and sexual orientations reflects a refusal to see art on its own terms[34]. What many intellectuals resist is that the arts have their own life, logic, and ideals[34]. The resulting attack on American aesthetic traditions undermined three pillars of our cultural sovereignty:

- Craftsmanship that connects generations through shared techniques

- Beauty that uplifts citizens by reflecting transcendent values

- Patriotic themes that strengthen national identity and common purpose

Reclaiming Our Art

America stands at a crossroads for reclaiming its artistic heritage. Throughout our nation, a quiet cultural renaissance has already begun, rooted in the revival of traditional skills and values that once defined American visual expression.

Call for a cultural revival rooted in craftsmanship, realism, and national heritage.

The resurgence of realism in American art signals a return to our authentic artistic traditions. Presently, evidence of this revival appears in gallery exhibitions, magazine coverage, and competitive art organizations like the Art Renewal Center and the Bennett Prize. A new generation of successful contemporary realist painters—including Roberto Ferri, Nick Alm, Jeremy Lipking, and others—has elevated the movement through works that combine technical achievement with conceptual depth[7]. Significantly, art schools called ateliers have swept across the country, restoring healthy bourgeois values to American art[8]. Within these studios, traditional drawing techniques flourish once again.

Reassert art’s role: to uplift the people, honor tradition, celebrate liberty.

Traditional art remains intrinsically linked to cultural identity, serving as a visual representation of our community’s heritage and reflecting beliefs deeply embedded within its members[6]. These art forms are living embodiments of cultural heritage—encapsulating customs, rituals, and wisdom handed down through generations[6]. Undoubtedly, art shapes collective memory, influencing how societies remember and interpret their past[9]. By reclaiming our artistic traditions, we reconnect with the values that built our Republic.

America can bury the frauds of Cultureburg and restore art that reflects the Republic.

Federal sites dedicated to history must become solemn and uplifting public monuments that remind Americans of our extraordinary heritage[4]. [44] Museums in our nation’s capital should inspire—not indoctrinate—igniting imagination in young minds and instilling pride in all Americans[4]. Forthwith, we must restore the Smithsonian Institution to its rightful place as a symbol of American greatness[4]. This cultural renaissance will generate jobs and livelihoods while promoting our cultural inheritance and social capital[10].

Conclusion

America stands at a crossroads between continuing down the path of artistic decay or reclaiming our rightful cultural inheritance. Throughout this examination, we have exposed how three unelected critics—Greenberg, Rosenberg, and Steinberg—orchestrated nothing less than a cultural coup against traditional American esthetics. Their deliberate dismissal of realism, craftsmanship, and beauty has severed generations of Americans from their artistic birthright.

Undoubtedly, this theft carried enormous consequences. Museums once filled with works that celebrated our national character now showcase pieces that confuse or alienate ordinary citizens. Universities train students to scorn beauty rather than pursue it. The realist masters who captured American life with dignity and skill have been relegated to the sidelines of art history.

The constitutional implications remain profound. A small Manhattan elite seized control of our cultural institutions without any democratic mandate. This closed cartel crushed the natural marketplace of artistic taste, replacing public preferences with incomprehensible theories. Their actions stripped America of visual traditions that once strengthened our shared identity and values.

Nevertheless, hope emerges from this cultural battlefield. Across our nation, a renaissance of traditional skills and esthetics gains momentum. Ateliers teaching classical drawing techniques have multiplied. Contemporary realists create works that combine technical mastery with meaningful content. These artists refuse to surrender American art to the frauds of Cultureburg.

We must reassert art’s true purpose: uplifting citizens, honoring tradition, and celebrating liberty. Our museums should inspire patriotism rather than cynicism. Federal institutions like the Smithsonian deserve restoration as monuments to American greatness, not laboratories for progressive experiments.

The battle for America’s soul continues on canvas as fiercely as in politics. Only when we demand art that reflects our Republic’s founding principles—beauty, order, faith, and freedom—will we truly reclaim our cultural sovereignty. The critics stole our artistic heritage without asking permission. The time has come for the American people to take it back.

Key Takeaways

This exposé reveals how three influential critics systematically dismantled America’s artistic traditions and replaced them with elitist theories that alienated ordinary citizens from their cultural heritage.

• Three unelected critics—Greenberg, Rosenberg, and Steinberg—orchestrated a cultural coup, replacing American realist traditions with abstract theories without public consent.

• “Cultureburg,” a closed Manhattan elite of critics and collectors, created an artificial art market that dismissed beauty, craftsmanship, and patriotic themes as “kitsch.”

• Museums now showcase confusing, degrading works instead of inspiring art. At the same time, universities train students to despise traditional values and technical skills.

• This cultural theft violated constitutional principles by seizing institutional control without a democratic mandate and crushing the natural marketplace of artistic taste.

• A renaissance of traditional realism and craftsmanship is emerging through ateliers and contemporary artists who reject elite theories in favor of beauty and meaning.

The battle for America’s artistic soul mirrors broader cultural conflicts. By demanding art that reflects our Republic’s founding principles—beauty, order, and liberty—Americans can reclaim their stolen cultural inheritance from the fraudulent theories of Manhattan’s art establishment.

FAQs

Q1. How did modern art critics impact traditional American art?

Critics like Greenberg, Rosenberg, and Steinberg fundamentally changed the American art landscape by promoting abstract and conceptual art over traditional realist styles. They elevated theory and process over technical skill and representational beauty, leading to a shift away from art that celebrated American values and traditions.

Q2. What is meant by the term “Cultureburg” about American art?

“Cultureburg” refers to the small, elite group of art critics, museum directors, and wealthy collectors in New York who wielded enormous influence over what was considered valuable art in America. This closed circle effectively dictated artistic tastes and trends, often at odds with popular preferences.

Q3. How did the rise of abstract expressionism affect American artistic traditions?

Abstract expressionism, championed by critics like Greenberg and Rosenberg, led to a decline in representational art and traditional techniques. It prioritized spontaneous, non-representational expression over craftsmanship and realism, significantly altering the direction of American art in the mid-20th century.

Q4. What impact did the shift in art criticism have on American museums?

The influence of modern art critics led many American museums to prioritize abstract and conceptual works over traditional realist paintings. This resulted in collections that often confused or alienated the general public, rather than inspiring or celebrating American culture and values.

Q5. Is there a movement to revive traditional American art styles?

Yes, there is a growing revival of realism and traditional techniques in American art. This includes the resurgence of atelier-style art schools teaching classical methods, as well as contemporary artists who combine technical skill with conceptual depth to create works that resonate with broader audiences.

References

[3] – http://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/what-did-leo-steinberg-do

[5] – https://www.brookings.edu/articles/defending-american-arts-culture-and-democracy/

[6] – https://dolapoobatgallery.com/blog/traditional-arts-timeless-preservation-of-cultural-heritage

[7] – https://observer.com/2025/05/realism-returns-art-market-museums-collectors/

[8] – https://medium.com/arc-digital/an-american-revolutionary-guide-to-21st-century-art-7ed1a48fccba

[11] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clement_Greenberg

[12] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_Rosenberg

[14] – https://www.theartstory.org/critics-greenberg-rosenberg.htm

[15] – https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-16-critics-changed-way-art

[17] – http://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/what_did_clement_greenberg_do

[18] – https://www.leslieparke.com/blog/greenberg-pollock

[19] – https://www.artforum.com/features/jackson-pollock-and-the-modern-tradition-part-iii-215307/

[20] – https://www.artsy.net/article/matthew-who-is-clement-greenberg-what-is-formalism

[21] – https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/action-painters

[22] – https://npg.si.edu/exh/brush/rosen.htm

[23] – https://www.theartstory.org/critic/rosenberg-harold/

[24] – https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/rosenberg-defines-action-painting

[25] – https://dokumen.pub/harold-rosenberg-a-critics-life-9780226740201.html

[26] – https://www.artforum.com/columns/leo-steinberg-2-198382/

[27] – https://www.americanheritage.com/when-pop-turned-art-world-upside-down

[28] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Painted_Word

[29] – http://cultureburg.com/about-cultureberg

[30] – https://glasstire.com/2016/06/05/on-elitism-a-conversation/

[31] – https://www.artrenewal.org/Article/Title/the-decline-of-the-visual-education-of-artists

[32] – https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/innovation-invention-and-free-market-creative-arts

[33] – https://fee.org/articles/the-arts-in-a-free-market-economy/

[34] – https://salmagundi.skidmore.edu/articles/436-authority-freedom

[35] – Clement Greenberg – Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clement_Greenberg

[36] – Bader, G. (2015). Top of the Pops. Artforum International, (), 39.

[37] – Harold Rosenberg Overview and Analysis | TheArtStory. https://www.theartstory.org/amp/critic/rosenberg-harold/

[38] – Harold Rosenberg: A Critic’s Life, Balken. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/H/bo22954988.html

[39] – Leo Steinberg. https://www.artforum.com/print/201108/leo-steinberg-29027

[40] – What Did Leo Steinberg Do? A Guide to Understanding the Brilliant Art Historian of “Other Criteria” | Art for Sale | Artspace. https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/know-your-critics/what-did-leo-steinberg-do-52470

[41] – *** MONDAY October 7th, 2019 *** The Price of Everything *** DIRECTED BY Nathaniel Kahn*** INTERPRETED BY Jeff Koons, Paul Schimmel, and Larry Poons | Cinematiki Maui. https://cinematikimaui.com/2019/10/05/monday-october-7th-2019-the-price-of-everything-directed-by-nathaniel-kahn-interpreted-by-jeff-koons-paul-schimmel-and-larry-poons/

[42] – On Elitism: A Conversation | Glasstire. http://glasstire.com/2016/06/05/on-elitism-a-conversation/

[43] – On Elitism: A Conversation | Glasstire. http://glasstire.com/2016/06/05/on-elitism-a-conversation/

[44] – Elia-Shalev, A. (2025). Jewish Cultural Institutions Reeling as Trump Defunds Arts and Humanities. Jewish Exponent, 137(51), 18-19.

Leave a comment